@joyphys

2018-02-06T00:30:54.000000Z

字数 6809

阅读 1592

化学工业起源于印度

MSArticle

原文链接:The origins of chemical industry

最早的工业化不在欧洲

One of the features of the Industrial Revolution was the translation of scientific laboratory techniques to viable industrial processes. This is usually regarded as a quintessentially European phenomenon – a product of the Age of Reason, with endeavours based on the results of reproducible scientific experiments and entrepreneurial industrialists.

工业革命的特点之一是将科学实验室技术转化为可行的工业流程。这通常被认为是一个典型的欧洲现象——理性时代(注:大致为西欧18世纪)的产物,以可重复的科学实验和实业家的商业经营为基础,一代代努力下实现的。

However, investigations have shown that such developments took place elsewhere more than a thousand years previously. Through similar means, the production of zinc by high temperature distillation was turned into a successful industrial process. The location for this birth of chemical industry? Northern India.

然而,研究显示,时间要追溯到更久远的一千多年前,地点也不是西欧,而是北印度,这里将实验室里的锌的高温蒸馏冶炼法成功转化为工业流程。

手稿线索

The production of zinc by conventional smelting methods presents considerable difficulties; instead of a liquid metal forming at the base of the furnace, zinc forms a highly reactive vapour (with a boiling point of 913°C) which exits the top of the furnace and promptly re-oxidises. Clearly, some method of containing and condensing the vapour out of contact with the air was needed – and our ingenious ancestors found a way.

用传统的冶炼方法生产锌是相当困难的,锌不会在冶炼炉底部形成液态金属(沸点913 ℃),而是成为反应活性很高的蒸汽,从炉顶排出并迅速氧化。显然,需要一些控制蒸汽不与空气接触并将蒸汽凝结的方法。我们在印度的祖先很有创造性,找到了一种方法。

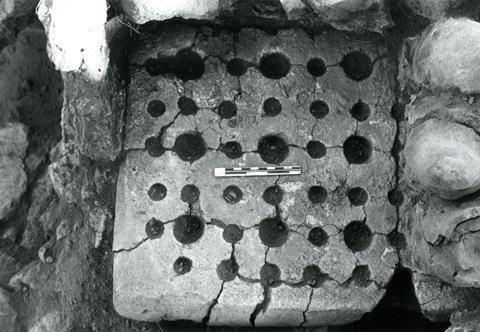

冶炼炉有四个多孔板,图为其中之一,反应罐位于板上,凝汽器颈位于比较大的孔中。

There are descriptions of the laboratory preparation of zinc in Indian medical treatises dating from the beginning of the first millennium AD.1 The zinc ore, together with a list of rather exotic organic ingredients, were to be placed in a clay retort set over a collecting vessel filled with water and heated with a charcoal fire. The forming zinc vapour condensed in this process of downward distillation. By the early second millennium AD, these descriptions had become more detailed. The retort was to be shaped like a brinjal, or aubergine, the condenser shaped like a datura, or thorn apple flower, and the zinc ore was shaped into small balls, still using the exotic organic ingredients.

从公元第一个千年初期的印度医学论著中有实验室制备锌的描述。将锌矿石与一系列奇特的有机物一起放入粘土反应罐中,反应罐用炭火加热,置于装满水的收集容器之上。蒸馏过程中,锌蒸气下行并冷凝。到了公元第二个千年初,这些描述变得更加详细。反应罐的形状像茄子,冷凝器像曼陀罗花,锌矿石被加工成小球,仍然使用那些奇特的有机物。

The process worked. In the 16th century, when most of the north of India had been absorbed into the Mughal Empire, a great inventory was prepared by the court chancellor Abū L-Faẓl Allāmī. The inventory, known as the Ā-īn-i-Akbarī, was completed in 1596, is India’s Domesday book. This work notes with interest, Jast, zinc, ‘is nowhere found in the philosophical books, but there is a mine of it in Hindustan, in the territory of Jālor.’

此工艺是行得通的。在十六世纪,北印度大部分地区被莫卧儿帝国吞并。帝国维齐尔(注:相当于宰相)阿布尔·法兹尔(AbūL-Faẓl Allāmī)编撰了《阿克巴治则》(Ān-i-Akbarī),这套著作完成于1596年,里面有锌冶炼的详细资料。《阿克巴治则》饶有兴致地写道,锌“在哲学书籍中没有记载,但是在印度斯坦,在贾洛尔(注:印度地名)的领土上有座锌矿。”

挖掘答案

The mine is in present-day Zawar, in the Aravalli Hills of Rajasthan. From the 20th century there were several geological and mining reports of extensive old mines, together with ruined walls built of old retorts. I therefore set up an archaeological expedition to investigate these remains, strongly supported by Hindustan Zinc, who had re-established mining in the second part of the 20th century.2

这座矿位于今天的印度拉贾斯坦邦扎瓦尔的阿拉瓦利山里。从二十世纪开始,关于这里大量的古矿井和反应罐壁遗迹,已经有多份地矿报告发表。因此,我成立了一个考古探险队,考察这些遗迹,考察活动得到印度斯坦锌业公司的大力支持,这家公司在20世纪下半叶重建了这里的采矿业。

印度扎瓦尔,冶炼炉发掘

The excavations revealed the remains of intact installations dating to the 14th century. But these weren’t for single retort smelting: they were major blocks of seven furnaces, each containing 36 retorts, allowing 252 retorts to fire simultaneously. It is estimated each retort produced about 100–150g of the metal per firing, meaning each furnace block could produce about 25–30kg of zinc per day. Later, improved furnace blocks were found dating to the 16th century, which contained 108 larger retorts probably produced about 50kg per day. With many such blocks working at once, peak production from the mines must have been several hundred kilograms per day.

这次考察发掘出了14世纪的完整装置的遗迹,这套装置不是单个蒸罐熔炼,而是由7个冶炼炉组成的炉组,每个冶炼炉包含36个反应罐,即可以有252个反应罐同时开工。据估计,每个反应罐每次开工可生产大约100-150克锌,即每个炉组每天可以生产约25-30千克锌。后来,又发现了可以追溯到十六世纪的改进炉组,每个炉组的反应罐更多,达到108个,且容积更大,每天大概能生产约50千克锌。许多这样的炉组同时工作,矿山平均每天的产量峰值可达数百千克。

Traditional processes around the world are often perceived as static, but that was certainly not the case here. The very first furnaces, dating from about 1000 years ago, had hand-made plates and condensers. In the later furnaces, these were always moulded with exactly the same dimensions and clearly must have been mass-produced in central workshops. While furnaces were still made individually, they had to conform to the precise dimensions of the components – clearly, the authority running the mines was asserting overall control and increasing efficiency. Similarly, the later mines were huge open cast operations that engulfed the earlier works.

世界各地的传统工艺流程往往被认为是静态的,但在这里,肯定不是这样。最早的一批冶炼炉可以追溯到大约1000年前,含有手工制作的炉壁和冷凝器。此后的冶炼炉,都是用模具建造的,尺寸精确一致,显然是在中央车间批量生产的。尽管炉子还是一个个建造的,但要求部件的尺寸精确一致。显然,矿山管理部门采取了强力措施对矿山施加整体控制和提高生产效率。类似地,再之后来的矿山进行大规模的露天作业,毁了早期的工场。

知识扩散

The mines of Zawar were certainly run by the state, and ultimately the Maharajah. The furnaces were probably run by individual operators, very likely belonging to the Jain sect, whose members, rather analogous to the non-conformist sects in 18th century England, were a merchantile and entrepreneurial class; at Zawar they were responsible for most of the temples. Clearly, the royal government was prepared to finance the development of a very radical process – the first high temperature distillation process anywhere in the world – from laboratory to the mines.

扎瓦尔的矿山当然是由国家管理的,最高管理者为大君(注:印度地方土邦最高统治者)。这些炉子大概是由个体户经营的,很可能是耆那教(注:印度古老宗教之一,比佛教更古老,并且对现代印度有较大影响。)信徒,耆那教成员与18世纪英格兰的不从国教者类似,为商业和企业家阶层。显然,帝国政府动员了各种社会资源,资助一件非常激进的事情——世界首创第一个高温蒸馏工艺——并且是从实验室到矿山的全链条开发。

The development of a laboratory technique into an industrial process must have had a strong incentive. Northern India lacks significant tin deposits and thus the usual copper alloy was brass rather than bronze. This would have been made by what was known in Europe as the cementation process, in which copper was reacted with zinc ore and charcoal in closed crucible.3 This process (which did not change until the 19th century) was very inefficient and produced a poor quality brass; brass made by mixing copper and zinc metals gave much greater control and a purer product, and thus Zawar zinc would have been prized.

将实验室技术发展成为一个工业过程,必须有强烈的动机。北印度缺乏大的锡矿床,因此常用的铜合金是黄铜(注:铜锌合金)而不是青铜。在欧洲,生产黄铜用的工艺是渗碳工艺,即铜在密闭坩埚中与锌矿石和木炭反应。这套工艺(一直沿用到19世纪)效率非常低,生产的黄铜质量很差。铜和锌混合不用碳制黄铜,可以对产物进行更好的质量控制,得到更纯的产品,因此在扎瓦尔锌倍受重视。

Sadly, a high tech process needs stable conditions in which to operate and retain and train highly skilled operatives. While production flourished at Zawar through the medieval period, it faltered following the Mughal invasion and slumped as political conditions in post-medieval India deteriorated. Eventually, the zinc was replaced by imports, initially from China and then from Europe. There’s a certain irony that the first viable European process for zinc, developed by the William Champion of Bristol, UK, and patented in 1742, was almost certainly based on knowledge of the Zawar process; what was long believed to be the first industrialisation of zinc was really selling the metal back to the true pioneers.

可悲的是,高科技工艺流程需要稳定的作业环境,保留和培养高技能的操作工。虽然中世纪时代的扎瓦尔的锌生产一度很兴旺,但在莫卧儿帝国入侵之后,随着后中世纪时代印度的政治条件的恶化,锌生产陷入衰退。最终,锌被进口取代,最初来自中国,后来来自欧洲。讽刺的是,欧洲第一个可行的锌生产工艺,在1742年获得专利,由英国布里斯托尔的威廉·钱皮恩(William Champion)开发,几乎可以肯定是基于扎瓦尔工艺的知识,但是却长期以来被认为是锌的最早的工业化流程,欧洲后来者把此工艺生产出的锌卖给工艺真正的开拓者——印度。