@ShixingWang

2016-05-13T09:25:30.000000Z

字数 7117

阅读 3308

Exercise 11: Precession versus Eccentricity

王世兴

2013301020050

Problem 4.11

Investigate how the precession of the perihelion of a planet's orbit due to general relativity varies as a function of the eccentricity of the orbit. Study the precession of different elliptical orbits with different eccentricities, but with the same value of the perihelion. Let the perihelion have the same value as for Mercury, so that you can compare it with the results shown in this section.

Abstract

The precession of the perihelion of Mercury is one of the first test for general relativity theory. Numerically we can treat the relativistic effect as a fix on the inverse-square law of gravitational force. Perihelion are found as the point where the position vector and velocity vector are orthogonal. The precession trajectories and the relationship of the precession angle versus time are presented with the parameter much larger than the true value. Under the same parameter the relaitonship between the angular speed of precession and the eccentricity of the trajectory are given and fitted with the function in the same form of the analytical relation.

Background

Precession of the Perihelion of Mercury

Under Newtonian physics, a two-body system consisting of a lone object orbiting a spherical mass would trace out an ellipse with the spherical mass at a focus. The point of closest approach, called the periapsis (or, because the central body in the Solar System is the Sun, perihelion), is fixed. A number of effects in the Solar System cause the perihelia of planets to precess (rotate) around the Sun. The principal cause is the presence of other planets which perturb one another's orbit. Another (much less significant) effect is solar oblateness.

Mercury deviates from the precession predicted from these Newtonian effects. A number of ad hoc and ultimately unsuccessful solutions were proposed, but they tended to introduce more problems. In general relativity, this remaining precession, or change of orientation of the orbital ellipse within its orbital plane, is explained by gravitation being mediated by the curvature of spacetime. Einstein showed that general relativity[2] agrees closely with the observed amount of perihelion shift. This was a powerful factor motivating the adoption of general relativity.

The total observed precession of Mercury is 574.10±0.65 arc-seconds per century[6] relative to the inertial ICFR. This precession can be attributed to the following causes:

The correction by 42.98" is 3/2 multiple of classical prediction with PPN parameters

Thus the effect can be fully explained by general relativity. More recent calculations based on more precise measurements have not materially changed the situation.

In general relativity the perihelion shift σ, expressed in radians per revolution, is approximately given by:[12]

where L is the semi-major axis, T is the orbital period, c is the speed of light, and e is the orbital eccentricity.

Main Features of the Codes

Object-Oriented Manner

We defined a classLorenzto include the initialization of parameters, calculation of the differential equations, display of phase plots and 3D animation. This is extra conventient when we change the parameters and repeat the same processes.Only One Cycle

To obtain the attractor in chaos phemonenon, we need to get two of the coordinates when the third is zero. This means judging and cycle structure is inevitable in the program, which is a terrible time consumer. We solve this problem by combining choosing points for the attractor plot with solving differential equations. In this way can we use only one cycle to give all the plots needed, while the drawback is also obvious that this program may take more memory.Inner Product to Find Perihelion

Unlike the trajectory in polar coordinates where we can easily find the perihelion as the point at which the differential of radius about angle is zero, we recognize the perihelion by the fact that as perihelion the position vector is orthogonal to the velocity vector.Errorbar Plot

Since every precession rate is obtained by fitting the curve of anglar shift versus time, there are errors in these values. So we plotted the errorbar plot in Figure 11.4. However, since the fine linearity of the data the error bar is too short to be seen.MATLAB Curve Fitting

MATLAB is a commercial software with powerful tools to fit almost all kinds of curves. Here we use a custome equation obtained in theResultsection to get a relatively good fit.

Results

Consisitence with the Results from Textbook

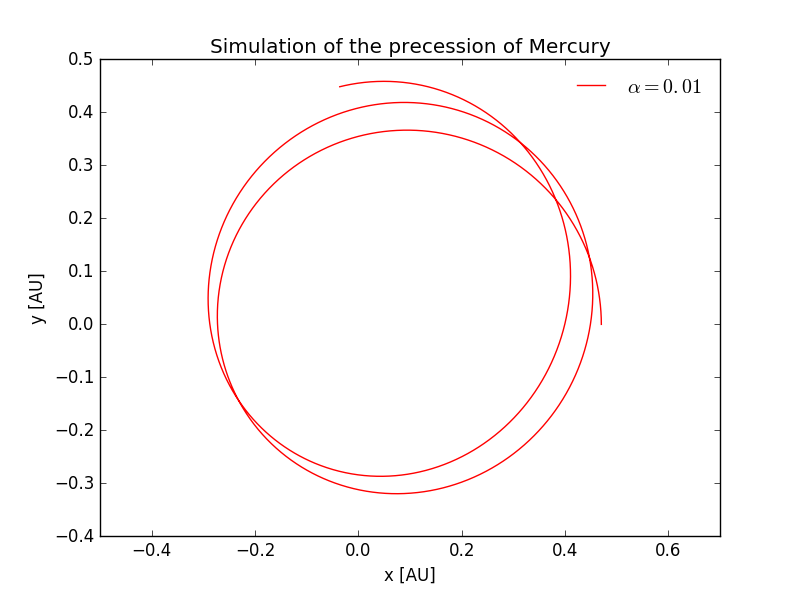

To check the correctness of our codes we choose the same parameters as those in the text book and plotted the figure of the trajectory of the "Mercury" when =0.01.

Figure 11.1 Simulated orbit of Mercuryorniting the Sun, with =0.01, the time step 0.0001 yr

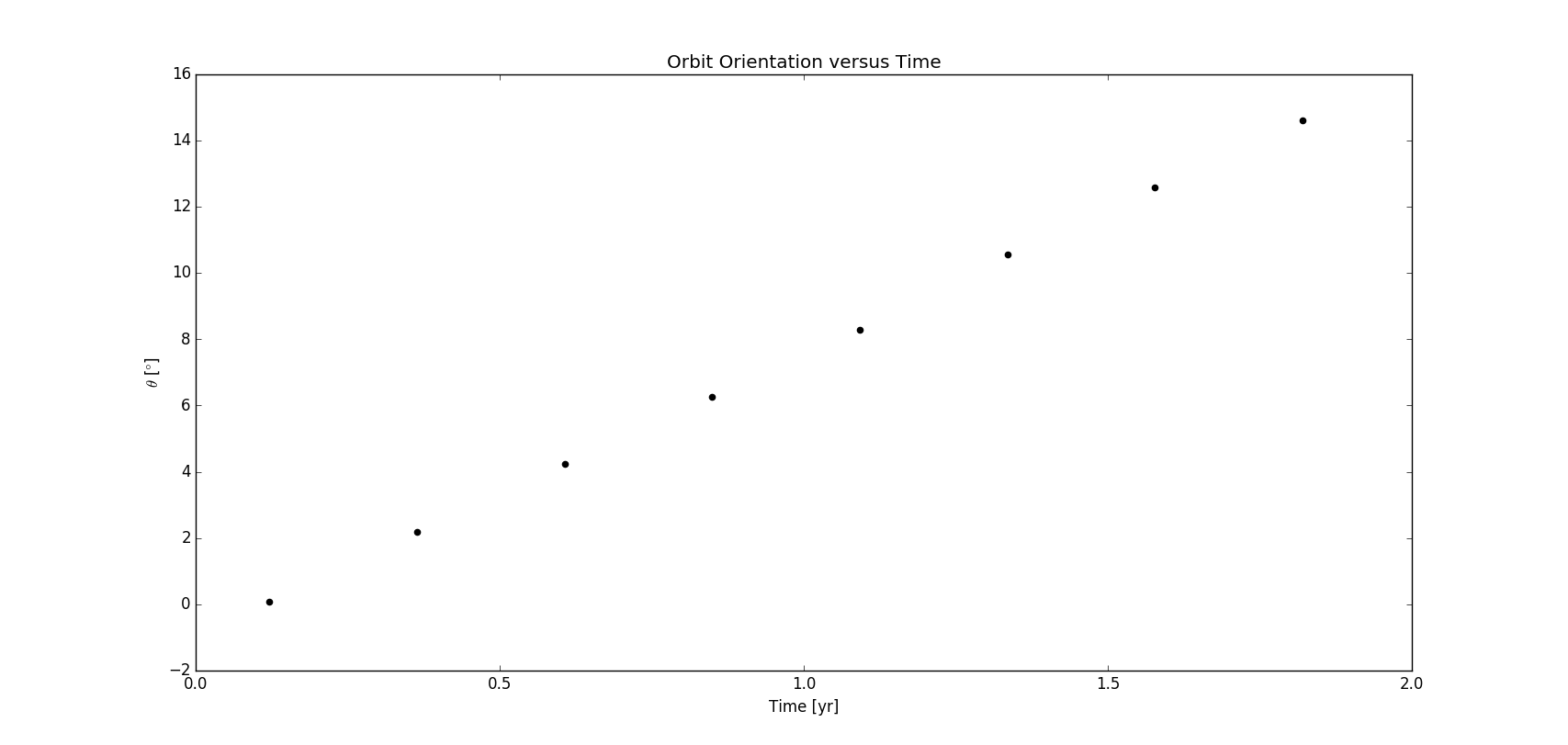

Then we change to be 0.0008 and obtain the scatter plot of the precession angle of the perihelion versus time in Figure 11.2

Figure 11.2 Precession of the axis of Mercury's orbit as a function of time, for =0.0008 and time step of 0.0001 yr

There is minor inconsistence between the result here and that in the textbook. Since we used the semimajor axis and eccentricity to calculate the perihelion and we have no idea what value the textbook uses for this parameter, we assume that this accounts for the difference.

Trajectories for Different Eccentricity

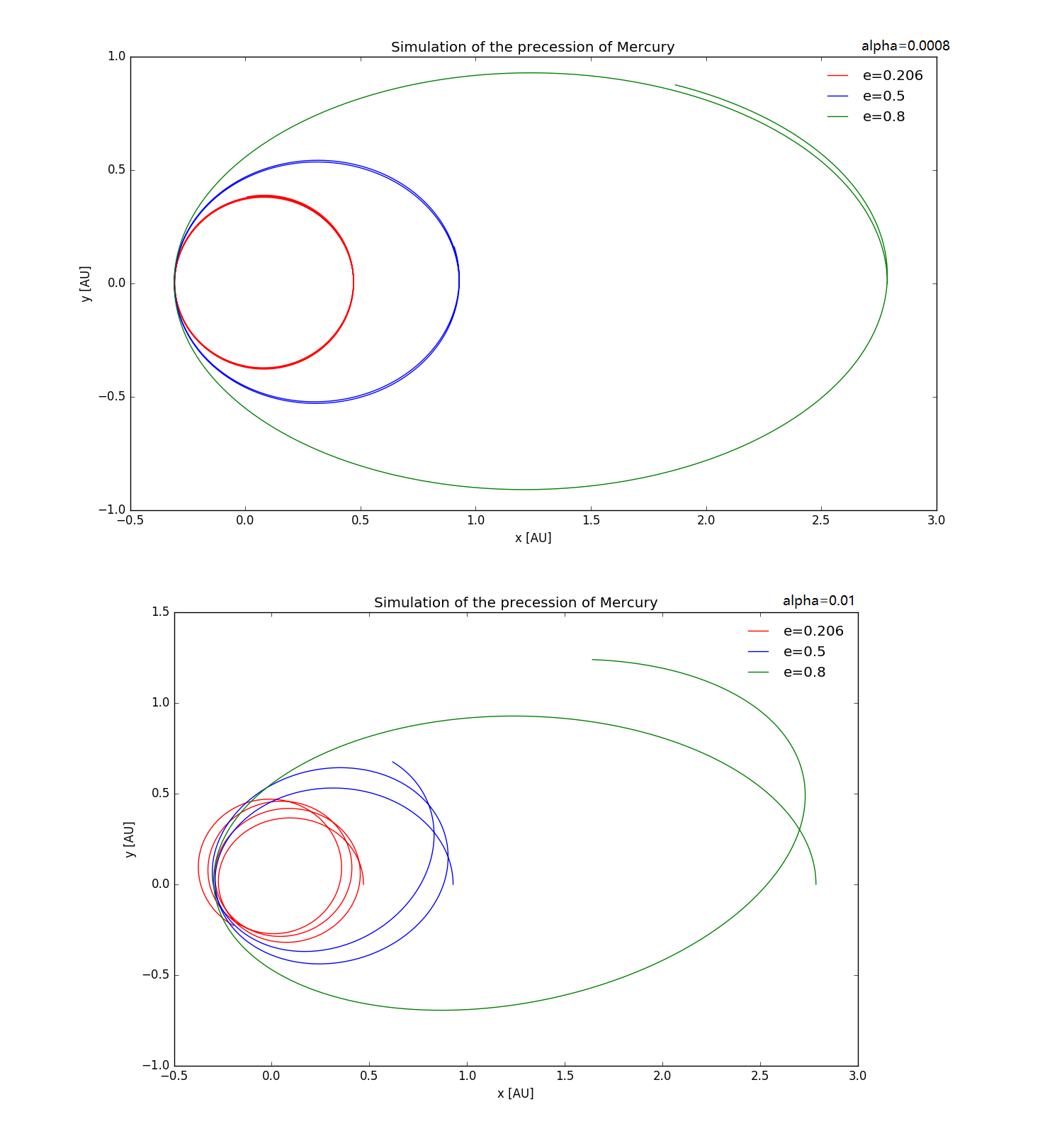

For interest we plot the trajectories under different eccentricities keeping the length of the perihelion the same.

Figure 11.3 Precession of the axis of Mercury's orbit as a function of time, for equals 0.0008 and 0.01 respectively, and time step of 0.0001 yr

Precession Rate as a Function of Eccentricity

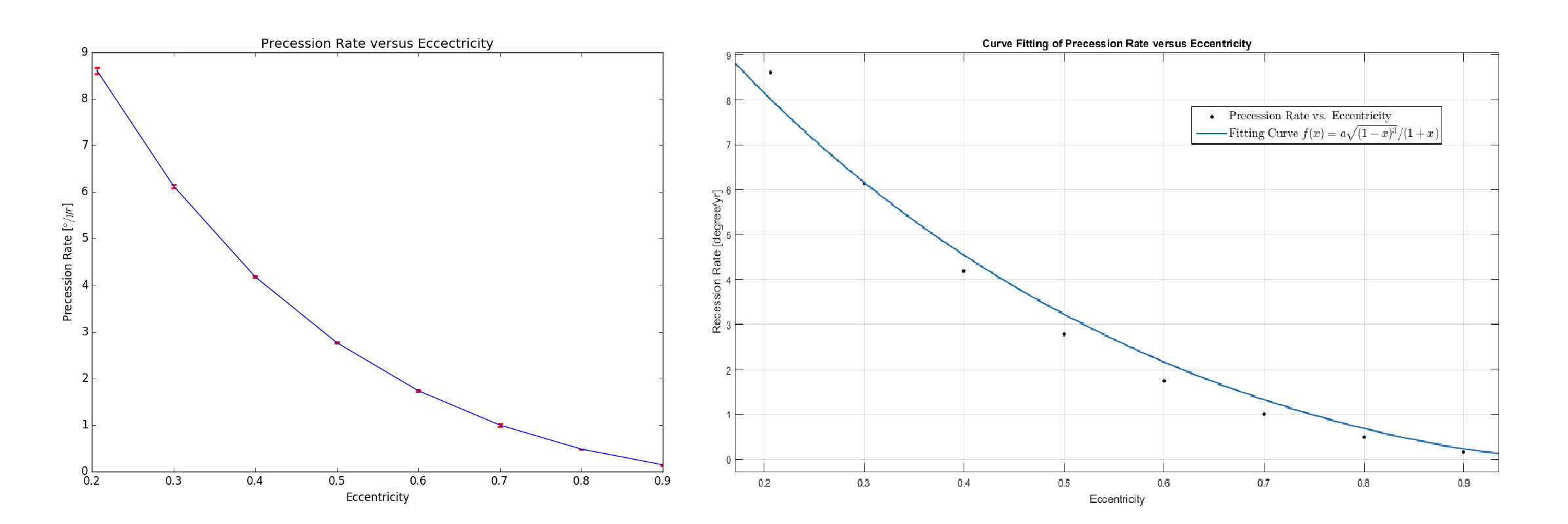

Here we define the precession rate as the angle deviation of the semiminor axis of the orbit in a unit time. The method to find the angle of the semiminor axis is introduced in the Discussion section. By changing the eccentricities we get a series of precession angle and the time. By fitting the tangent of the dots we get the precession rate and its upper and lower limit with 95% confidence.

| Eccentricity | Precession Rate (degree/yr) | Lower Limit (degree/yr) | Upper Limit (degree/yr) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.206 | 8.609 | 8.536 | 8.681 |

| 0.300 | 6.129 | 6.095 | 6.162 |

| 0.400 | 4.183 | 4.161 | 4.204 |

| 0.500 | 2.769 | 2.750 | 2.789 |

| 0.600 | 1.737 | 1.720 | 1.755 |

| 0.700 | 0.999 | 0.970 | 1.028 |

| 0.800 | 0.483 | 0.483 | 0.483 |

| 0.900 | 0.146 | 0.132 | 0.160 |

Chart 1. the relationship between the precession rate and the eccentricity. =0.0008, perihelion=0.3AU

From the equation in the introduction section, perihelion shift σ, expressed in radians per revolution

the since the perihelion is fixed, the semimajor axis has a relation with the eccentricity

And according to the Kepler's Third Law

Our precession rate should be

By experience function fitting of MATLAB we get a fitting curve with R-square of 0.9839.

Figure 11.4 (left)The errorbar plot of the precession rate and time, the errorbar is too short to be conspicuous; (right) the fitting curve with function

Reference

Wikipedia contributors. "Tests of general relativity." Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 23 Apr. 2016. Web. 8 May. 2016.

Einstein, Albert (1916). "The Foundation of the General Theory of Relativity" (PDF). Annalen der Physik 49 (7): 769–822. Bibcode:1916AnP...354..769E. doi:10.1002/andp.19163540702. Retrieved 2006-09-03.

Clemence, G. M. (1947). "The Relativity Effect in Planetary Motions". Reviews of Modern Physics 19 (4): 361–364. Bibcode:1947RvMP...19..361C. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.19.361.

Dediu, Adrian-Horia; Magdalena, Luis; Martín-Vide, Carlos (2015). Theory and Practice of Natural Computing: Fourth International Conference, TPNC 2015, Mieres, Spain, December 15-16, 2015. Proceedings (illustrated ed.). Springer. p. 141. ISBN 978-3-319-26841-5. Extract of page 141